Some of the ideas I put forth as bucket list suggestions require leadership skills.

There is a huge difference between a leader and a boss.

A boss is someone who tells you what to do, and you do it only because you want to keep your job. You do not necessarily have any respect for the boss.

Leaders are called to see the forest when others can only see the trees. A leader doesn’t just give orders. A leader forms a plan, using all available resources.

A leader is someone who inspires you to follow, to work together to achieve a common goal.

Some people are born leaders. Others develop the qualities of leadership by learning from the example of others who have inspired them.

And, of course, there are those individuals who only think they are leaders.

When I was growing up, we lived on a farm in Southern Illinois, and the entire place was one ginormous playground. Acres and acres of rolling hills, pasture, ponds, hay and corn fields and fence lines with tall trees where we could romp. Sheds and barns filled with all sorts of dangerous chemicals and equipment for us to play with, on, and around. Stacks of hay to climb, jump and fall from. It was great.

That was back in the days when western movies and television shows like Rawhide, with Clint Eastwood as Rowdy Yates, and Gunsmoke, starring James Arness as Marshall Matt Dillon, dominated the entertainment industry, along with a few war stories which could be seen every week on shows like Combat!, starring Vic Morrow as Sergeant Chip Saunders. So, quite naturally, when we kids played, we were either cowboys or soldiers.

One particular summer day, back in the early to mid 60’s, when I was about eleven or twelve years of age, my younger brother and I were playing Army with our neighbor, Richard, who had come over for a few hours.

Richard was the born leader of our group. By that, I mean he was born earlier than my brother or I, so being the oldest made him the leader. Sergeant Richard. I, being next in line, was a corporal. My little brother, Jimmy, was a private.

We were patrolling the farm with our toy guns. I with my Johnny Seven O.M.A. (One Man Army), Jimmy with his very real-looking Tommy gun, and Richard with an equally realistic toy rifle, looking for enemy soldiers. It was mid-summer, hot and humid, but we were on a mission. We saw plenty of action that day, as they were everywhere.

We had just finished clearing out an enemy machine gun nest in our barn. Not a difficult task for a soldier armed with a Johnny Seven. I mean, this weapon could do it all. It featured a machine gun, a rocket launcher, as well as a grenade launcher. It had a tripod-mounted rifle and as if that wasn’t enough, it even had detachable pistol. All other outbuildings were already secured. Only one remained. The hog house.

Richard was a good friend. Fun to be around, and as make-believe Army sergeants go, not a bad sort of fellow to follow into battle. If I could find one fault in his leadership style, it would be that he didn’t consult the men who were taking orders from him.

Had Sergeant Richard chosen to consult Corporal Wayne Baker and Private Jimmy Baker, he might have learned some valuable information that would have certainly factored into his plan of attack.

You see, what Jimmy and I knew that our leader didn’t was that there was a hazardous no-man’s land between our concealed position in the barn and the heavily fortified hog house.

Normally, when we had hogs in the hog house, there was what we called a slotted floor I front of it. Basically, the slotted floor consisted of a 20’ by 40’ section of flooring made up of 2 x 6” wooden planks with about an inch of gap separating them. On this floor, Dad kept the automatic hog feeders, large bins shaped more or less like a funnel. The feed, which consisted of ground up corn, a cost effective, low fiber feed, high in digestible carbohydrates. The feed would slide down in the feeder, where the pigs could gain access to it by lifting cover lids with their noses. When they were satisfied, they would walk away and the lids would fall shut with a metallic clang. It was a simple yet effective arrangement. The lids protected the feed from rain, snow, rats and birds.

The idea behind the slotted floor was that the hogs would walk out onto it to eat from the feeders.

Most of their excrement would be dropped onto this slotted floor and from there down through the slots into a pit beneath it that was about three feet deep. The whole thing was built on skids.

When the hogs reached market weight, the would be shipped out. Market weight on feeder pigs is in the neighborhood of somewhere around two hundred and eighty pounds. Figuring an average dressing percentage of about seventy-five per cent, that would yield two-hundred-ten pounds of meat, more or less.

After the hogs were all shipped out, Dad would then hook it up with a chain to the old orange Allis-Chalmers model WD45 tractor to the skid and pull it away from the hog house, then use the scoop on the tractor to dip out the pit into the manure spreader. From there the hog manure was taken to the field and used as fertilizer.

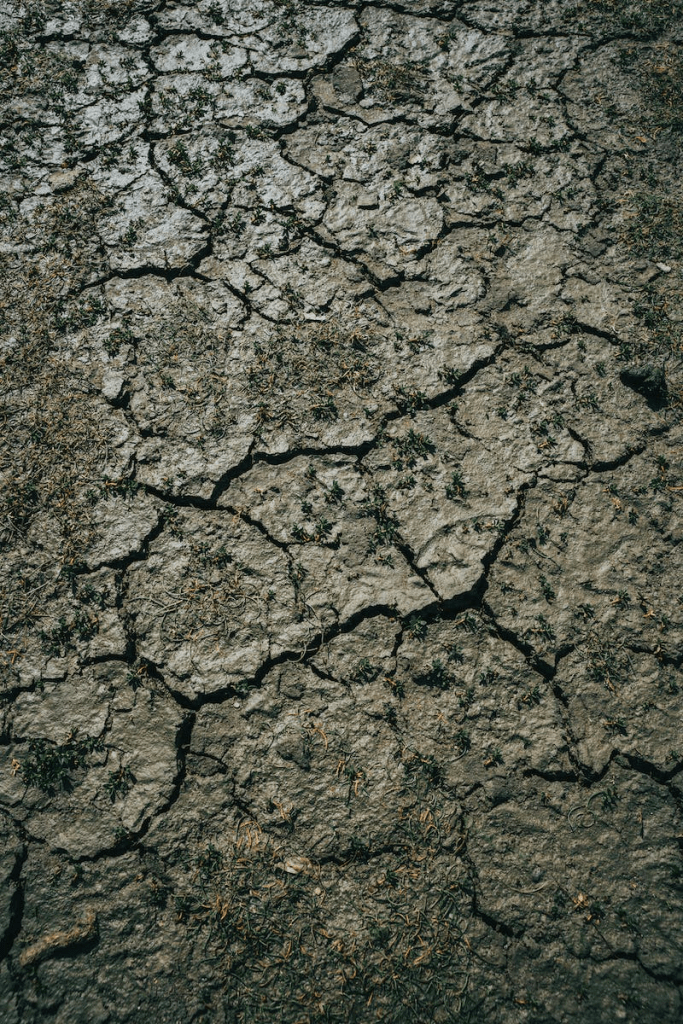

The hogs had gone to market a couple weeks prior. Dad had already pulled the slotted floor away. But he hadn’t yet gotten around to dipping out the pit.

Sitting there, exposed to the summer sun, the top inch or two of the hog manure had dried out, forming a crust and causing it to look just like the rest of the solid ground in the hog lot.

I knew that. My little brother Jimmy knew that. But, Sergeant Richard did not know that. He didn’t ask, and before we could mention it, he yelled, “FOLLOW ME, MEN!” and charged as fast as his feet could carry him toward the hog house.

I looked down at Jimmy.

Jimmy looked up at me.

We stood there, mesmerized, unable to call out to our leader. We watched helplessly as Richard ran right into the manure pit. He made it about two steps before becoming stuck, crotch-deep in hog manure. I don’t know how, but he somehow managed not to fall face first into the muck.

Dad was on the tractor, cultivating corn in the eighty acre field just north of the house, and just happened to look toward us just in time to see it all happen. He tried waving his straw hat and shouting for Richard to stop, but he didn’t hear him. None of us did. I suppose the distance was too great for his voice to carry over the sound of the tractor’s engine.

As Richard was pulling himself out, covered from the crotch down in a mixture of blackish, blueish, sticky muck consisting of hundreds of compounds created in the intestines of the pigs who had a few short weeks prior. Hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and methane, now released into the atmosphere as a delightful symphony of aromas. Dad used to always say that was the smell of money. Those hogs paid a lot of bills for us back then.

We tried not to laugh at our friend Richard. I swear, we tried not to laugh. But that was impossible. During his efforts to extricate himself from the muck, Richard lost one of his boots, and none of us bothered to try to retrieve it.

I believe that anyone aspiring to become a leader can take some valuable lessons from what happened that hot summer day back in Southern Illinois.

First, I will give my friend Richard credit. You can’t lead others where you won’t go yourself, and he certainly did go before us without fear or trepidation.

As I said before, though, leader doesn’t just give orders. A leader forms a plan, using all available resources. On that day, he could have asked questions. He could have consulted with the men he was leading into combat. Had he done so, he could have learned of a natural hazard that ultimately led to the failure of his accomplishing his mission.

With the intelligence my brother and I could have provided, he could have put an alternative plan in place. It would have been quite easy to have flanked the hog house from both sides, avoiding the manure pit altogether. Which he certainly would have done had he consulted his men, the local citizenry.

And he didn’t have an exit strategy, just in case things didn’t go according to plan.

I remember Dad driving up, shutting down the tractor, and saying with a grin, “Well, Richard, it could have been worse.”

Richard looked up to him and said, “How in tarnation could it have possibly been any worse?”

Dad replied with a chuckle, “It could have happened to me!”

I felt sorry for Richard. I was laughing, but nonetheless, I felt sorry for him. Neither his mother nor ours would drive him home, for obvious reasons. He had to walk that half-mile back to his house, covered in hog manure, over loose gravel, with only one boot.

Leave a comment